Cancer sequencing panels are key molecular tools in modern oncology. They make it possible to detect genetic alterations relevant for diagnosis, prognosis, and the selection of targeted therapies. In this article, I explain what an oncology sequencing panel is, how it identifies mutations, and when a patient should consider having one done.

What is a cancer sequencing panel?

A cancer sequencing panel (an oncology NGS panel) is a targeted genomic test that simultaneously analyzes a defined set of genes involved in cancer development, progression, or therapeutic response. Unlike whole-genome sequencing, panels focus on genes with clinical relevance—actionable mutations, fusions, amplifications, and deletions—which allows clinically applicable information to be obtained more quickly and cost-effectively.

How a cancer sequencing panel works to identify mutations

Sample collection: tumor tissue (fresh biopsy or formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded—FFPE) or liquid samples such as ctDNA (circulating tumor DNA) in plasma.

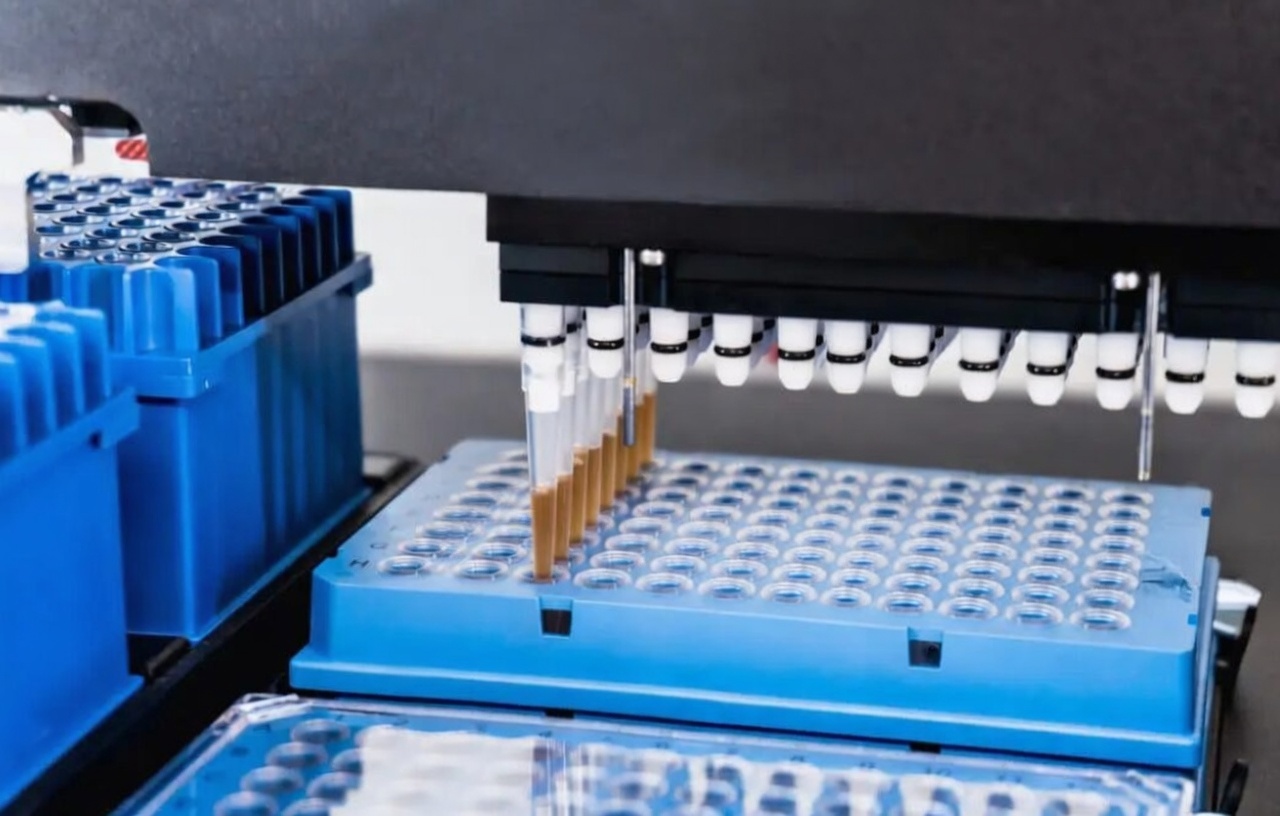

DNA/RNA preparation and extraction: purification of nucleic acids suitable for the technique.

Target region enrichment: exons/genes included in the panel are selected through hybridization capture or PCR amplification.

Massively parallel sequencing (NGS): enriched molecules are sequenced in parallel, generating short reads that cover target regions at high depth.

Bioinformatic analysis: reads are aligned to a reference genome, variants (SNVs, indels), rearrangements, and copy-number changes are detected, and filtered by quality.

Clinical interpretation: variants are classified according to clinical evidence (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, of uncertain significance), and actionable mutations, therapeutic options, clinical trials, and prognostic relevance are reported.

Validation and reporting: quality controls, validation of critical findings when appropriate, and generation of a clinical report with recommendations.

Main types of alterations detected

Point mutations (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels).

Copy-number variations (amplifications or deletions).

Gene rearrangements/fusions (e.g., ALK, ROS1).

Alterations in DNA repair genes (BRCA1/2, MMR) and genomic signatures (TMB, MSI when the panel allows).

In liquid tests: identification of ctDNA with mutational profiles representative of the tumor.

In short, it is a focused NGS test that analyzes multiple cancer-relevant genes to detect clinically meaningful genetic alterations that can guide diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

When should a patient consider undergoing a cancer sequencing panel?

A patient should consider an oncology sequencing panel in the following situations:

Diagnosis of advanced or metastatic cancer: to identify actionable mutations that enable targeted therapies or immunotherapy.

Tumors with known targeted treatment options: when there are approved therapies or clinical trials aimed at specific genomic alterations (e.g., EGFR, ALK, BRAF, BRCA).

Relapse or progression after standard therapy: to detect resistance mechanisms and choose second-line treatments or the right clinical trial.

Patients with suspected hereditary cancer syndromes: if the test includes predisposition genes or is complemented with germline testing.

When non-invasive monitoring is desired: use of liquid panels (ctDNA) to track response and detect early recurrence.

Selection for biomarker-based clinical trials: many studies require specific alterations to be present.

Cases of uncertain diagnosis or rare tumors: where genomics can provide diagnostic or management-relevant information.

Conclusion

Cancer sequencing panels are practical and powerful tools for identifying relevant genomic alterations that guide therapeutic and monitoring decisions. They should be considered especially in advanced/metastatic cancer, progression after treatment, suspected hereditary predisposition, or for clinical-trial selection. Choosing the right panel type, ensuring sample quality, and performing proper clinical interpretation are essential to maximize the test’s clinical value.